Haifa before & after 1948 – Narratives of a Mixed City

Genesis of the Haifa Project

The Haifa project and subsequent publication “Haifa before & after 1948 – Narratives of a Mixed City“ was developed throughout 2008-2011 at a time of social and political strain in Israel. During meetings held in Salzburg, Hamburg and Tel Aviv, fourteen Israeli and Palestinian experts from the fields of Middle Eastern history, social and economic history, anthropology, sociology and architecture were paired with their respective national counterpart. At the conclusion of these meeting the scholars had collaborated successfully to create seven shared historical narratives on the economic, social, cultural and political life of Haifa in the 1948 period.

It was a group decision by the authors to restrict their research to the micro-perspective and thus shift focus away from the resolution of the conflict. The principal challenge for many authors was compromising on their narratives. The research questions were determined by the availability of sources such as archival materials, press reports, interviews and ethnographic studies. The articles address history and memory, focusing on the links between these issues and the individual and collective identity of Israelis and Palestinians in the pre- and post-1948 periods. The chapters expand from the individual level to the community, and then come back to the individual.

Full PDF of the article

Historical Background

In order to understand the references and events that are discussed in the articles, historical “milestones” are provided to assist the reader. In 1840, the Ottomans resumed control over Palestine after the Egyptians left and made Haifa the center of a district. As a result, the city became the main harbor and center for foreign trade. In 1868 German Templars began immigrating to an area of the city that became known as the German Colony. The 1880s saw European Jews begin to immigrate to northern Palestine. As the Ottoman Empire continued to open up to the west, European officials and merchants began to settle, bringing about further development. As the economic infrastructure improved, the city increased in administrative importance, which in turn led to an intensification of immigration from abroad and emigration from within Palestine of people from all socio-economic levels. Palestinians called Haifa Umm al-Gharib, meaning ‘Mother of the Stranger’. Further development came in 1905 when construction of the Hijaz railway finished and Haifa became a major rail terminus.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Haifa was the leading city of Palestine. Because of its status and advanced development, Jewish immigrants settled in the city bringing Jewish-owned heavy industry that changed the economic base of the city. In 1908 the Ottoman Empire allowed the publication of newspapers making Haifa a major journalism center. As the population increased, new neighborhoods were built to accommodate the demand.

The British Mandate period, 1918-1948, had a significant impact on the city. Mandate initiatives included building a modern harbor, airport, and railway workshop in addition to pipelines and refineries for Iraqi oil. The city’s population was both religiously and ethnically diverse, consisting of Christians from all churches, Muslims, Jews, Syrians, Lebanese, Jordanians, Egyptians, Sudanese and Europeans. In 1918 the city’s population was 22,000 of which one eighth were Jewish. By 1947 Jews made up half of the 140,000 residents. The growth in population altered the cultural composition of the city with Arabs no longer forming the majority. In 1936 there was a slump in the building industry which affected both Arab and Jewish unemployment, but it was the subsequent Arab strikes that provided employment opportunities for Jews who seized the opportunity to work in traditionally Arab professions.

The authors agreed that regardless of political views, the fall of Arab Haifa in 1948 constitutes one of the key events in Nakba. For the Palestinians the fall of Arab Haifa symbolized the end of the Palestinian urban life. It saw seventy-four thousand Palestinians forced from their homes, leaving only two to three thousand, who were relocated to a specific area of the city. For the contemporary Jewish narrative, Haifa is still a symbol of Jewish-Arab co-existence, without reference to the events of 1948. This is a significant difference.

The Articles

The first article by Mahmoud Yazbak and Yfaat Weiss, A Tale of Two Houses, uses the story of two houses to show the Palestinian narrative of before and after the Nakba on a micro-level, through the experiences of the owners of the houses and their tenants. After the establishment of the State of Israel, most Palestinians either fled or were forced out of the city and were not allowed to return. The minority remaining were forced into the Wadi al-Nisnas neighbourhood. Any property left behind was placed under state control and in some cases Jews and recent Jewish immigrants were allowed to reside in the abandoned homes.

The first home in the article was the house of Fadil Ahmad Shiblak on 1 Lod Road. The house was located in the area known as the “seam line”, an area between Hadar ha-Camel and Wadi al-Salib neighborhoods. During the mandate period there was a building boom, and the authors show how this house was part of it and was built to provide extra income to the owners and mitigate the housing shortage. Rather than follow traditional Palestinian architecture, the building was designed to hold multiple families separately, which was a style that started in Jewish neighborhoods and took hold in Palestinian ones. Forty-seven people lived in the building on Lod Road; Jews and Palestinians lived together and underwent the same hardships during the economic downturn of the 1930s and Axis bombing during World War II. In 1948, Fadil Ahmad Shiblak and his family were forced to leave, and after being labelled refugees they were kept from returning home. The authors provide biographical details of how the Shiblak family dealt with refugee life and the many moves they were forced to make. This story exemplifies the life of a building owned by a Palestinian.

The other house, Hanna Swindon House on 33 Crusader Street, was built in the 1930s. The family was forced to leave in 1948, but was able to retain ownership of the property. The experience of this house and family highlight the relationship between the owners and tenants who wanted to adapt the property to their needs. The history of the house also shows the “mismatch” that occurred between high quality buildings and the low economic status of their tenants. The house is part of the Palestinian story in that the owners were economically well off and had done well under the Mandate governments; it also enters the Jewish story, as the state tried to deal with the stream of immigrants from Europe and the Arab world by placing them in any available space.

The second article, Arab-Jewish Architectural Partnership in Haifa during the Mandate Period: Qaraman and Gerstel Meet in the “Seam Line” by Waleed Karkabi and Adi Roitenberg focuses on architecture and the professional and personal relationship between the Jewish architect Moshe (Morris) Gerstel and Palestinian-Arab entrepreneur Hajj Tahir Qaraman. The article goes into detail about Gertsel’s “international style” of design, the structures he built, and finally the fate of his structures. Gerstel became the “house architect” for Qaraman, designing business and personal buildings. At one point Gerstel even lived on the roof of Qaraman’s home. After 1948, Qaraman’s property was transferred to new Jewish tenants. Those of Gerstel’s buildings built in the Carmel survive in good condition today, yet those in the “seam”, an area that has developed into a slum, are falling into disrepair.

These buildings and the relationship between Gerstel and Qaraman show how much influence the decision to demolish or conserve historical buildings can have on people’s memory. Determining what is worthy of remembrance ends up influencing the city’s narrative.

The third chapter, Arabs and Jews, Leisure and Gender, in Haifa’s Public Spaces, by Manar Hasan and Ami Ayalon instead focuses on sociology by looking at the relations and social ties between Arabs and Jews in the 1930s and 1940s. This was a time of social change and national conflict, but also of modernization and increasing public space with new sporting facilities, theatres, cafes and restaurants being built.. On a macro-level there was separation between communities, yet both mixed residences and mixed relations in the workplace remained. The authors found that both Arabs and Jews tend to view pre-1948 daily realities through the prism of later events. Two shared spaces that the authors examined in detail were cinemas and soccer stadiums. Evidence revealed that there were two separate sets of leisure patterns that had limited overlap as movies were chosen and advertised to the groups differently due to language and cultural tastes.

As for football, the first documented match between an Arab and Jewish team was in 1919. By 1928 there were 70 Arab and Jewish teams nationwide. Press accounts provided information of the matches and showed how there was little reporting on inter-group contests and far more attention paid to intra-group matches. The authors also found that the 1920s had the highest level of interaction, while by the 1940s it was less common to see a match between the two groups.

The authors also look at Israeli and Palestinian women in spaces of culture and leisure and investigate the question of whether the two groups mingled. Cafes, beaches and restaurants were places attended by women and one can assume interaction would have taken place. Scouting through the Girl Guides of Palestine was one activity the authors looked at to support the increased presence of women and girls in public spaces. They concluded that women were limited to a shared use of space, yet did not forge any social relationships with ‘the Other’ be that Arab or Jew. One chooses to engage in leisure activities and they are consequently more susceptible to social and political changes. The authors also concluded that cultural and recreational life of the two groups ran parallel. Towards the end of the mandate, the groups became more distant and alienated.

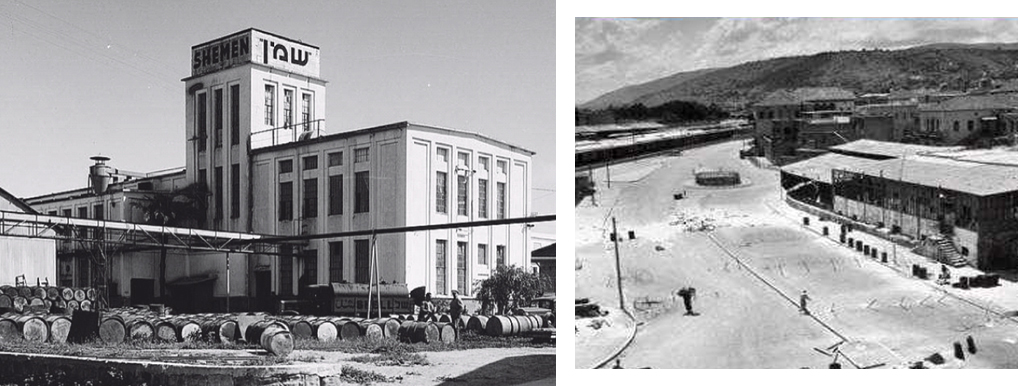

The narratives shift again in the fourth chapter to economic history in Commodities and Power: Edible Oil and Soap in the History of Arab-Jewish Haifa by Mustafa Abbasi and David De Vries. The economy and its improvement played a significant role in the development of Haifa into a major city and port. The article explores this through the edible oil and soap trade. Prior to the British Mandate’s involvement in influencing the edible oil and soap trade, Haifa was just a marketing spot for traditional Nablusi oil and soap. The high price of the products, high acidity relative to other oils from the Mediterranean region and limited storage life kept the development and trade of the industry local. As the city developed, production factors improved and there was a growth in volume and a change in the character of consumption. As the city developed, Arab families who ran the oil business moved to the city and laid new commercial infrastructure. After World War I and the establishment of the British Mandate, the mandate government supported the Jewish National Home initiative and worked to develop the administrative infrastructure, which caused economic and social changes.

It was during this period that the Jewish-owned company Shemen opened a factory in Haifa, hiring only Jews. It is difficult to compare the Jewish and Palestinian oil industries. The imbalance in historiography is due to the traditional focus of Arab merchants on home-based production, trade and local consumption versus the large-scale Jewish industrial production and export that provided more evidence of activities. As a result of British economic policies, Shemen was able to mitigate initial problems in the production, import and export of materials for the oil and soap trade, whereas Arabs were unable to participate. This improved Shemen’s competitiveness and dominance in the industry. For Palestinians, 1948 marked the end of their participation in the oil and soap economy, while Shemen continued. The article shows how mandate-era economic policies influenced the economic and social developments of the two communities in Haifa.

The fifth chapter sees the narratives turn to the effects of 1950’s severe winter weather in Dan Rabinowitz and Johnny Mansour’s Historicizing Climate: Haifawis and Haifo’im Remembering the Winter of 1950. The article looks at how the weather event resonates in the memories and narratives of the two groups. Outstanding Climate Events (OCE) can become significant benchmarks in keeping time, and can affect wider cultural sensibilities and identities. The authors used archival materials, literary pieces, newspaper articles and interviews with Israeli residents, Palestinian residents and refugees. This particular OCE is known as Sana al-Thaljih to Palestinians and Horef Hamishim to Israelis. The event was framed in three different ways. The first of which saw the event framed as a novelty and departure from expected patterns. The Jews viewed it as a memorable benign event, whereas the Palestinians were more subdued and the event was colored by the hardships of exile, such as poor shelter. The second was adversity. Both sides characterized it as part of their struggle to survive as individuals and as a nation. Jewish newspapers characterized it as a continuation of 1948 struggles. Finally, the event was framed as a test of individual and collective endurance. For Israeli Jews it was proof of institutional resilience as they had assistance to deal with the effects of the weather, whereas the Palestinians had no support and in this sense the weather event highlighted the results of 1948.

In the next chapter, Salman Natour and Avner Giladi write about two cultural institutions in Haifa in “Eraser” and “Anti-Eraser”- Commemoration and Marginalization on the Main Street of the German Colony: The Haifa City Museum and Café Fattush. The article looks at how the Haifa City Museum and Café Fattush address memory and identity. The authors analyze official publications and documents in addition to a mix of observation, impression, and personal memoir. They tell the story of the institutions both in terms of their development and their relationship with the historical quarter in which they are located. The authors provide historical context for the area termed the “German Colony”.

Starting as a colony for German Templars, it later became a center of Arab culture during the Mandate and then finally was taken over by Israeli Jews. The history and changes can be seen in the architecture of the buildings and the change in street names. The Haifa City Museum is located in the former Templar Community House, built in 1870. Its official mission is to address the urban history of Haifa. Programs and exhibits tend to serve the Zionist narrative at the expense of others, particularly the Palestinian narrative. This narrow focus even goes as far as to highlight the German Colony’s contribution to the city without mentioning the anti-Semitic views of the German inhabitants before and during the Mandate period.

Finally, the authors turn to Café Fattush which is located on Ben-Gurion Boulevard with the City Museum. The café opened in 1998 and attracted artists and intellectuals, and eventually hosted symposiums, poetry readings, festivals, cultural evenings, exhibits and theatre productions. Although met with obstacles, these events provided a space for Palestinian cultural expression. The violence from the second intifada of October 2000 and the second Lebanon war in 2006 led to a decrease in co-mingling between Palestinians and Jews in these cultural areas. The museum and the café both attempt to preserve and develop a collective memory, with different goals in mind.

The last article, Haifa Umm al-Gharib: Historical Notes and Memory of Inter-Communal Relations by Regev Nathansohn and Abbas Shiblak, brings the focus back to the individual, specifically on memories. The authors use interviews with Haifa residents born in the 1930s, secondary literature and personal family experiences. The aim of the article is to show Haifa’s two-fold experience of solid inter-communal relations and strategies of segregation. The dominant narrative of 1948 stresses the rupture between the two communities, yet empirical evidence shows it was not quite this simplistic. Both traditional Israeli and Palestinian narratives not only stress this rupture narrative but are also organized to deny the shared Jewish-Palestinian relationship throughout the war. The authors believe that the dominance of nationalism should not suppress moments of intersubjectivity.

From a historical perspective, during the late Ottoman period memoirs refer to Arab-Jews mixing with Arab-Muslims who enjoyed the same culture, spoke the same language and celebrated religious festivals together. Even until 1948 there was a term for Jews of Arab descent, Yahud Awlad ‘Arab. At the turn of the twentieth century, indigenous Jews did not necessarily identify themselves in national or ethnic terms. It was during the British Mandate that the economic transformation of the city affected group dynamics and relations. The economic competition between the two groups, and the parallel track they were on did not provide much opportunity for positive interaction. The oral histories presented by the authors reveal moments, opportunities, denials and deferrals of the social interactions between Jews and Palestinians that occurred during the increasing violence of the 1930s and 1940s. The interviews also provided essential insight into the period. Oral history can offer perspective on events that are different from general historiographies based on military, state and diplomatic archives. The interviews presented in the article come from Christian-Palestinians and Jews who were children in the forties. The mix of interviews and historiography reveals the complex understanding of events and group relations that existed at the end of the Mandate.

Contributors:

Editors

Mahmoud Yazbak is a professor of Palestinian History, head of the department of Middle Eastern History at the University of Haifa.

Yfaat Weiss is a professor at the department of History of the Jewish people and is the former head of School of History at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Authors

Mustafa Abbasi is a lecturer at Tel Hai Academic College in Upper Galilee.

Ami Ayalon is a professor of Middle Eastern history at the Department of Middle Eastern and African History, Tel Aviv University.

David De Vries is professor at the Department of Labor Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University.

Avner Giladi is professor of Islamic Studies in the Department of Middle Eastern History, University of Haifa.

Manar Hasan is a lecturer of sociology at Zefat Academic College and the Program for Gender Studies at Bar-Ilan University.

Waleed Karkabi is head of the building conservation team in the Haifa municipality.

Johnny Manour is a lecturer at the History Studies Department at Beit Berl Academic College, Israel.

Salman Natour is an author and playwright.

Dan Rabinowitz is an anthropologist writing on ethnicity and nationalism, the Palestinian citizens of Israel, the Arab-Israeli Conflict and the nexus between environment and society.

Adi Roitenberg graduated from the Neri Bloomfield Academy of Design (“Witzzo”) in Haifa as an architectural practical engineer.

Abbas Shiblak is a scholar and human rights advocate.

Regev Nathansohn is a PhD candidate in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.