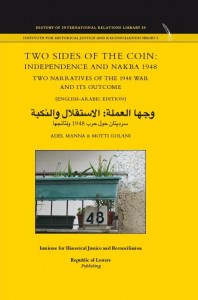

Two Sides of the Coin: Independence and Nakba 1948

Two Sides of the Coin: Independence and Nakba 1948, by Professor Motti Golani and Dr. Adel Manna, contains two national narratives of the 1948 War and its outcomes: one Jewish-Israeli and the other Palestinian. The framework for this project was first conceptualized in 2004, but socio-political realities pushed its development to 2009. Over a two-year period, Professor Golani, a Jewish-Israeli, and Dr. Manna, a Palestinian of Israeli citizenship, collaborated on a shared narrative. It was not an easy process, as noted in the introduction: “The attempt to formulate one text consisting of two different and often contradictory stories was emotionally challenging for both of us, as it required each of us to take part in formulating a narrative that was contradictory to our own respective experiences and education and that often challenged our respective identities” (21). Despite the challenging process the UK newspaper The Independent recognized the publication in 2012 as one of the year’s best history publications. Furthermore, the author’s enthusiasm for the project went well beyond the publication of the text to its continued promotion through speeches at universities in Israel.

Two Sides of the Coin: Independence and Nakba 1948, by Professor Motti Golani and Dr. Adel Manna, contains two national narratives of the 1948 War and its outcomes: one Jewish-Israeli and the other Palestinian. The framework for this project was first conceptualized in 2004, but socio-political realities pushed its development to 2009. Over a two-year period, Professor Golani, a Jewish-Israeli, and Dr. Manna, a Palestinian of Israeli citizenship, collaborated on a shared narrative. It was not an easy process, as noted in the introduction: “The attempt to formulate one text consisting of two different and often contradictory stories was emotionally challenging for both of us, as it required each of us to take part in formulating a narrative that was contradictory to our own respective experiences and education and that often challenged our respective identities” (21). Despite the challenging process the UK newspaper The Independent recognized the publication in 2012 as one of the year’s best history publications. Furthermore, the author’s enthusiasm for the project went well beyond the publication of the text to its continued promotion through speeches at universities in Israel.

PDF Version of the publication.

1948 Narrative

The authors start by presenting two anecdotes that show how deeply significant the events and terminology of 1948 remain today. While delivering a lecture, a historian was told by the audience to use the term ‘Nakba’ instead of ‘1948 war’. The other story reveals that Israeli military leaders continued to use the term ‘War of Independence’ during confrontations at the turn of the twenty-first century to connect the present to the past.

The authors point to the events of 1998, the fiftieth anniversary of the State of Israel, as triggering the Israeli tendency to look to the War of Independence for solidarity and for Palestinians to remember the loss of their homes and Nakba. The narratives from the period have been used to deepen and possibly eternalize the conflict.

The book then focuses on the Jewish and Palestinian-Arab inhabitants of Mandatory Palestine, which saw the majority of the fighting barring some slight incursions into South Lebanon and the Sinai Peninsula. The narrative chapters in the book typically use each side’s narrative definitions as they understand them and tend to employ them. The authors decided to interweave these terms to better facilitate understanding between one another. This decision highlights points of contention as well as similarities that would otherwise not be as evident. The authors do not distinguish one narrative from another so it is not always obvious whose narrative is being presented.

The narratives in the book were chosen because of their prevalence in the last twenty years. The authors worked to find an ‘average’ narrative so that the text would reflect dominant opinions from both societies. They also agreed to a basic historical and geographical framework. This framework focused on the narrative of events in Mandatory Palestine from 1947 to the late 1950s. Context to these events is provided by reviewing historical events from as far back as the mid-nineteenth century.

The origins of the two narratives are different. Much of the Palestinian narrative is still framed within the confines of local histories with little reference to the broader contexts that are generally used to construct a collective identity. It is difficult to accommodate the various Palestinian historical narratives due to the split between leaders in Gaza and the West Bank. For the Jews, there are multiple narratives and sources from the Israeli education system, defense, academic scholars, literature, film, non-governmental organizations and the media. The Jewish-Israeli narrative has benefited from state-sponsored institutional agents of memory, while the Palestinian narrative lacks a comparable dominant institutional narrative. The Palestinian narrative of Nakba views the events of 1948 as a trauma that defines their identity and national, moral and political aspirations. It has also led to a victimized national identity. Palestinians feel that they are paying for the European Jewish Holocaust rather than those responsible. The Jewish-Israeli perspective of the War of Independence is current rather than historical. It is perceived as an act of historical justice and the birth of a nation; therefore, it must be pure and untainted to ensure the state’s legitimacy. The authors emphasize that the narratives are not merely the result of the war, but also fuel the ongoing conflict.

About the Authors:

Dr. Adel Manna is the director of the Academic Institute for Arab Teacher Training at Beit Berl College. His research focus includes the history of Palestine in the Ottoman period and more recently Palestinians in Israel during the first decade of Israeli statehood. Until 2007 Dr Adel Manna was the director of the Center for the Study of Arab Society in Israel at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute.

Professor Motti Golani teaches at the Land of Israel Studies, Haifa University. His most recent research focuses on the end of the British Mandate in Palestine in 1945-1948: The End of the British Mandate for Palestine, 1948, Palgrave Macmillan and St. Antony’s College, Oxford 2009; while The Last Commissioner, Alan Gordon Cunningham, 1945-1945, TAU & Am Oved 2011 (Hebrew) is to be published by UPNE in English.